Attentional processes

We all have the feeling of being overwhelmed sometimes. It might be because our colleague insists on telling us all about his last vacations while we are already trying to focus on that urgent email and attempting not to obsess over that important document we haven’t finished yet; or it might be because our kid keeps on asking us pointless questions and that our significant other refuses to turn down the sound of the television while we are trying our best to concentrate on that novel we’ve been dreaming of staring for weeks but never had the time…

Whether in our professional or personal life, we are continuously “bombarded” by a tremendous amount of perceptual information. However, our information process capacity is too limited to consciously deal with the entirety of the continuous flow of information coming from multiple sources. How do we deal with that? How do we still function when exposed to so much information? How do we manage to select important information while ignoring the non-relevant ones acting as parasites? All these questions have been at the core of multiple researches in cognitive psychology for years and still provoke numerous debates and disputes today because experimental studies on the matter are far less easy to realise than it seems. Despite all that, the fact that there is indeed an optimisation of the information treatment via a selection and inhibition process is a consensus in the scientific community.

William James defines “attention” as “Taking possession by the mind, in clear and vivid form, of an object or a sequence of thoughts among several that seem possible […]. Involves the removal of certain objects in order to deal more effectively with others.”

Selective attention

One solution to avoid being overwhelmed by an excessively large amount of information, is to focus on a very specific part of the information (the sound of a voice, a color …) and select it to give it a sort of processing priority. This is what we commonly call “selective attention” and it corresponds to the focusing of our cognitive resources on an information or a piece of information deemed relevant. Meanwhile, information deemed parasitic are ignored.

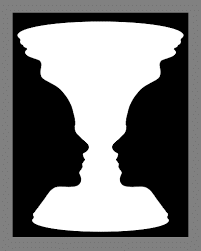

An example of this process can be illustrated by the images allowing multiple interpretations such as the famous Rubin Vase. Indeed, depending on the part of the image on which we focus our attention, we can see alternately a vase or two profiles facing each other. We can only perceive one interpretation of the drawing at a time because when our focus is on one part, the information that allows us to see the other image is inhibited.

Selective attention is somehow a process we can summon at will and that allows us to focus on a specific part of the information we receive. However, even if our objectives and intentions are clear and defined, other information, if sufficiently remarkable can seize our attention and distract us (e.g. a sudden noise).

A question arises then. When our attention is focused on something, do we actively suppress distractions or do we simply ignore them while letting them exist in the background? In other words, what happens to the information that we do not pay attention to?

To answer this question, we will take a look at an effect well known to psychologists: The Cocktail Party Effect.

Imagine yourself being in a noisy room, where many conversations are on-going, such as at a gala or a celebration. You are in the middle of a conversation and you can focus on the words of your interlocutor without much difficulty. Thanks to your selective attention, you instinctively ignore all other conversations around, which are yet perfectly audible and could be distracting. However, when a person that is not part of your conversation suddenly pronounces your name, your first reflex is to turn immediately towards them, even though you were not aware that you were hearing them up to this point. You react to the enunciation of your name because it has a strong emotional value for you and therefore it constitutes a remarkable stimulus. This is what we call the “Cocktail Party effect”. The case of a Name is commonly used as an example to explain this effect, but it is not the only type of stimulus allowing us to observe it. Indeed, the perception of a particularly intense or incongruent stimuli, whether visual (e.g. a camera flash going off suddenly) or auditory (e.g. a glass breaking noisily) leads to the same result. And the same goes for other stimuli with significant emotional values such as obscenities or calls for help.

This effect shows us that if we are able to focus our cognitive resources on a relevant portion of the information, the rest of the information is not entirely erased, but rather processed at a subconscious level and even if only a small part of it has a sufficiently high alert value to catch conscious attention, the information that was being processed is relegated in the background to give way.

This Cocktail Party effect shows us that we can differentiate two types of attention factors. The endogenous attention, when the person subjectively and voluntarily directs their attention to an information based on their motivation and intention, and the exogenous attention that consists in the automatic and objective seizure of the information regardless of the will of the person. The latter generally occurs in the treatment of sudden and salient information (e.g. a door slamming abruptly).

Divided attention or multitasking

Another extremely interesting area of this subject concerns divided attention. Unlike selective attention, it allows us to perceive an action as a whole or to collect information from multiple sources or events. In this case, instead of processing one information very precisely, we will deal with a multitude of information in a more superficial way in order to obtain a more global understanding, even if incomplete, of a situation. Divided attention enables us to absorb much information from a complex scene or from multiple simultaneous events, but at the expense of the accuracy of the information.

In summary

The attention is a dynamic process that involves the upgrade or the selection of a particular information and the inhibition of another. It can be seen as a control mechanism for the use of our limited cognitive resources in order to avoid being overwhelmed by an overpowering amount of information.

Example of an experimental study: The Stroop test

This test is a classic when it comes to the study of Attentional processes and it is used in particular to study the inhibition and control of interference.

Instructions: Start by reading each word out loud once, from left to right.

Then, start again from the beginning, but this time by naming only the colors in which the words are written, disregarding their meaning.

Thanks to this fun exercise, we can easily realize the gymnastics our brain has to go through when selecting information and inhibiting parasites.

The Attentional processes is one of the many topics that fascinates us at 3R Consultants.